Hypnotizing Nature in Hariye Jawa and Pasangmara

লেখক: Aditya Banerjee

শিল্পী: Team Kalpabiswa

The Dilemma Between Science, Nature, and Literature Too

Progress is a corollary to sacrifice. Science has given us rational amusement and partially eclipsed the magical effect of unnatural phenomena. With the invention of scientific gadgets, human intervention in the forbidden territories of nature has increased, significantly leading to the destruction of ecological balance. The recently published article, Ghostly Past and Colonial Uncanny by Tithi Bhattacharya fetches our attention to some narratives of Rabindranath Tagore’s Chelebela (Boyhood, 1940), where Tagore narrates about the bygone days of his supernatural belief about Brahmadaitya (a Brahmin Ghost). Tagore’s narrative juxtaposes the condition of Calcutta with its modern arrival of lights and the childhood faith in supernatural existence associated with the veil of a dark and shabby environment. Science, with its rationality, brought light to remove darkness, and the cloak of supernatural faiths was slowly torn. With experimental success, science has successfully faded the power of fear, and death, and also provided the key to controlling earthly features for commercial purposes. Though the main purpose of the paper is not to discuss ghostly tales, the introductory lines will set the plethora for the discourse of scientific limitations and the almightiness of nature. Nature, which is both cradle and grave for living beings and has caged unexplained phenomena, tolerates the disastrous experiments and destructive footprints of humans. Even in the prenatal stage of many discoveries, science-fantasized writers write about adventurous expeditions and surprising machinery to reduce human effort. With these notions of scientific imagination, the genre of science fiction developed and transformed its shapes with multiple waves. But even among the several categories that SF developed from a cartographical expedition to post-apocalyptic, ecological consciousness remained an intriguing factor. Modern science fiction has shown pedagogical approaches towards ecological literacy and the monstrosity of nature. Hence, the reason for choosing Tagore’s Chelebela is to show that science demands human intervention into the unknown territory of nature but with the conservation of nature and its primitive nudity, we can archive cultural histories and have some nostalgic effect too. While moving outward from the daily routine, these trips often heal us or give us something relishable. What SF has shown us in many texts, is a futuristic vision of such technological supremacy and a binary of utopian and dystopian scenarios. Specifically, while dealing here with two Bengali stories, certainly Satyajit Ray’s speculative fiction hero, Professor Trilokeshwar Shonku can be erected as a perfect example, who not only lives in a marginalized area (far from the humdrum of city life), named Giridih (presently in Bihar) but also prefers to lead a life who has got moksha from materialistic pleasure of life.

The Beauty and Wrath of Nature

The story I have selected here, Hariye Jawa (They Were Lost) by Anish Deb, portrays a futuristic vision of a city dominated by artificial intelligence. Forest X, the central character of the story, is a reserved forest kept for scientific expeditions every 100 years. The story says that for the last 250 years, people have detached from nature, and consumed foods and drinks manufactured in the laboratory. Even the atmosphere is covered with a synthetic cloak where everything is mechanical and produced according to requirement only. During such an operation to Forest X, a team of scientists never returned from the woods. Das, the protagonist of the story, is sent to the jungle to seek those lost scientists. Even it was decided if Das failed to return, Forest X would be blasted fully. Initially, Das travelled to Forest X with gadgets, ammunition, and medicines, but after meeting with those lost scientists in that dense forest area, his scientific temper of Das got dismantled. He started to imagine how a sunset could impact a person or the cold breeze of the forest could be so effective. The condition of the four scientists who failed to return to the central station of the city was surprising according to Das.

Das says, “Oh! What a pathetic condition of the four great scientists! Ranabir Sen, a famous entomologist, what has happened to him!” Ranabir Sen, the famous entomologist, wanted to die in the lap of nature, not under machinery surveillance. Choosing such a place where death comes with bliss can be considered a liminal zone where, before the last breath, nature purifies the soul from knowledge, the knowledge that destroys the magic of nature and its healing power. The story picturizes the differences between a life centered around calculative technological steps and the methods of survival in a primitive environment, where dresses were leaves and foods were hunted animals.

Nature, which has been exploited and controlled by humans since the dawn of civilization, can nullify human intervention with its power. Das referred to this as “Mohini Prakriti” or hypnotizing nature, as all scientific endeavours were lost due to nature’s hypnotizing beauty. Das undressed from protective suits and armours and dressed like an ancient man of the Stone Age. The cold streams, mountains, and breezing woods pacified the rational minds of scientists, and nature was projected as supreme. Ursula K. Heise asserts that ecological analysis is not limited to a narrow canon of nature writing. In a letter in PMLA’s 1999 Forum on Literatures of the Environment, she writes, “Ecocriticism analyses how literature represents the human relation to nature at particular moments of history, what values are assigned to nature and why, and how perceptions of the natural shape literary tropes and genres.” Heise continues, “One of the contemporary genres in which questions about nature and environmental issues emerge most clearly is science fiction… science fiction is one of the genres that have most persistently and most daringly engaged environmental questions and their challenge to our vision of the future.”

While choosing the second story, Pasangmara (a local/tribal deity of nature) by Taradas Bandopadhyay, for a comparative discussion, what ran through my mind was also the question of nature’s supremacy and human intervention. Plotted in a jungle situated near Simdega, Jharkhand (formerly part of Bihar), a team of surveyors visited to measure the land for industrial settlements. Within a few days, they started experiencing supernatural activities and resistance. The story centers around Pasangmar’s grudge against the officials who tried to remove the jungle. Taranath, a practitioner of esoteric activities, suggested to the narrator of the story one night to pack up their tools as soon as possible and evacuate the place. The continuous deterioration of the weather also gave them a reason to do so. Finally, with the arrival of Amarjiban, a person with some divine power, the author of the story and the officials are convinced that the place is not for human beings. Amarjiban asked Mejokarta (the officer in charge) to light a cigarette, but the wind resisted him from doing so. Amarjiban finally said, “Some places are not for humans. If they try to dominate, problems will come…some lives could be destroyed.” One day, the author of the story, while sitting inside the tent due to unstoppable rain, thought about humans in primeval society who sheltered inside caves and watched these natural phenomena with fear and mysteries in mind. The story symbolizes that the effects of scientific discoveries and mechanical footprints can be nullified by nature if nature wants to do so. Bishua, a labourer in the team, lost his memory for a few hours while roaming inside the jungle. Pasangmara, the tribal deity, is believed to be a saviour of the forest who will not spare intruders. This story, like Deb’s, symbolizes the idea that scientific discoveries and mechanical footprints can be nullified by nature if it so chooses. The story also highlights the limitations of human capacity in the face of nature’s supremacy. Pasangmara, the tribal deity, is believed to be a saviour of the forest who will not spare intruders. Similarly, in Deb’s story, nature’s “Mohini” or hypnotizing power stops the scientist, while in Bandopadhyay’s story, nature proves itself superior to the civilized race.

Drawing the Line

As Engels warns in Dialectics of Nature, “We should not be intoxicated with our victory against the natural world. For each victory, nature has retaliated against us. For each victory, we got our expected result indeed at the first step. But at the second or the third step, there are completely different and unexpected impacts, which often eliminate our previous achievements.” Had the surveyor team ignored nature’s hints, they could have faced dire consequences. William Leiss’s The Domination of Nature (1972) argues that Francis Bacon formulated the modern agenda of power over nature through science and technology, highlighting technology’s role in mastering both the external world of nature and human beings.

Bookchin, a green activist and socio-ecological theorist, notes that “The notion that man must dominate nature emerges directly from the domination of man by man…The plundering of the human spirit by the marketplace is paralleled by the plundering of the earth by capital.”

Both stories present nature as a space where human power is dissolved, and humans escape to a surveillance-free zone. Governance fails in both stories, with extraordinary machinery governance in the former and human governance in the latter. Nature projects itself as a governing body that knows how to secure the welfare of the population, improve its condition, and increase its wealth, longevity, and health. Pasangmara, who obstructs the team’s exploitative activities, also saves the natural organisms. Similarly, in Deb’s story, nature compels the scientists to lead a primitive life. The story concludes by highlighting the submissive attitude of humans towards nature’s incredible organic features, which science cannot reproduce, and demonstrates how life can be simple and death can be peaceful under natural governance. The location of Forest X on the periphery of the city underscores the importance of natural conservation, even if we marginalize it, nature is always ready to soothe us if we submit to it.

Conclusion

Before concluding the article, a famous analogy can be employed to connect the two stories once more. Plato’s Cave theory, where prisoners consider shadows as reality, can be seen as a parallel to the scientists in Deb’s story, Hariye Jawa. The prisoners, accustomed to darkness since childhood, never experience the external world’s reality. Similarly, scientists, controlled by artificial intelligence, fail to understand nature’s reality and nakedness.

In Sumana Roy’s article, “When Plato meets Guru Dutt,” the song Yeh Duniya Agar Mil Bhi Jaye toh kya hai(What will happen even if we get the world?) from the film Pyasa (1957)is compared to the chained prisoners. Roy suggests that those chained in materialistic pleasures cannot comprehend the enlightened soul of a philosopher like the poet Vijay. Likewise, the scientists in Deb’s story, invaded by nature, will find it uncomfortable to return to technocratic regulations. The four scientists, including Das, who never return to the station, are psychologically invaded by nature. Their experience of raw natural effects will make them uncomfortable with technocratic regulations, similar to the freed prisoners who feel blind after returning to the caves. The scientists were familiar with maps of the forest and its features, but their experience of nature’s power will be misunderstood, like the chained prisoners who thought the freed prisoners were harmed by nature. In Pasangmara, the author didn’t reveal the supernatural experience to his group, as their minds couldn’t absorb it. When he returned to Kolkata, his friend didn’t believe in Taranath’s bilocation. The supernatural experience enlightened the author’s soul, realizing that every place is not for humans, some are dominated by nature. However, he fears revealing the supernatural existence, lest his teammates consider him insane like his fellow prisoners thought the freed prisoners were harmed by the external world. As Foucault said, “Power is everywhere,” but the clash of power and the winning of the supreme one decides the fate. If nature fails to hypnotize and stop humans, it will exercise its power to destroy, as seen in devastating incidents like Kedarnath or Assam. Conservation is crucial to maintaining ecological equilibrium and empowering every organism in nature, ensuring that we don’t lament what we have lost. By focusing on mutual empowerment, we can supply future generations with the beauty of nature.

Notes:

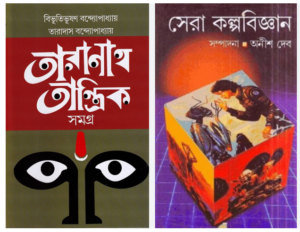

- The story Pasangmara is taken from the collection of Taranath Tantrik published by Mitra and Ghosh (2019), Kolkata.

- The story Hariye jawa is taken from the collection Sera Kalpabigyan (Best science fiction), 2021 published by Ananda Publishers Private Limited, Kolkata.

- The song Yeh Duniya Agar was sung by Md Rafi and composed by Sahil Ludhianvi.

References:

- Barker, Philip. Michel Foucault: An Introduction. Edinburgh University Press, 1998.

- Bookchin, Murray. The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy. Edinburgh: AK Press, 2005. Print.

- Engels, Friedrich. Dialectics of Nature. 1883. Progress Publishers, 1940. Print.

- Foucault, Michael. Discipline and Punish: The British Prison.Trans.Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage, 1977

- Heise, Ursula K. “Letter.” PMLA, vol. 114, no. 5, 1999, pp. 1096-1097.

- Roy, Sumana. When Plato meets Guru Dutt. The Indian Express ( Delhi Edition). PressReader.com – Digital Newspaper & Magazine Subscriptions, 2024