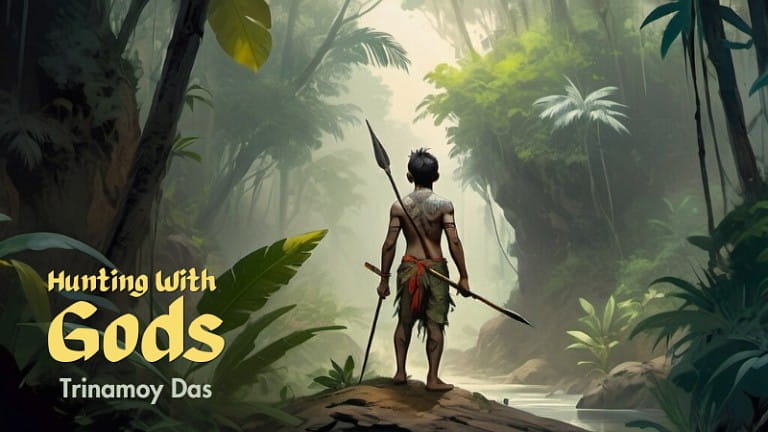

Hunting with Gods

লেখক: Trinamoy Das

শিল্পী: টিম কল্পবিশ্ব

The forest groaned under the summer sun. Leaves rustled. Twigs snapped. Birds sang. Insects hummed. Vikkel walked softly, the sound of his footsteps lost in the thick undergrowth. He kept his spear poised and his godmind open. Everything around him was alive with secret movements—a fine day for hunting.

“Above you,” his god whispered. Vikkel looked up and saw the grey form of a silver monkey. It sat on a branch, oblivious to the world, and chewed on a piece of violet leaf. The sagging shape of an animal past its prime.

“Not what I am looking for,” Vikkel whispered, his tone accusatory. He didn’t need to speak aloud to communicate with his god, but he still had difficulty with his non-verbal speech. Mudda would’ve scolded him if she had seen him now, talking loudly to the god while hunting.

“Use your mind,” she would’ve said. “He and you are always meant to be together, for you two are the same. Two shards of one blade. You don’t need to talk aloud to communicate.”

Vikkel wished that wasn’t true. He didn’t particularly like his god. Avuktha the Hungry, a god of the lower echelon. At the awakening ceremony, the priest pounded an obsidian nail through his heart, pulled it out, and begged the Gods of Gagganam Halls to bless the kid before he bled to death on the ceremonial stone altar. Vikkel had been happy that the gods had blessed him—not everyone survived the ceremony, but that was before a lowly god had spoken inside his mind with a flat, bored voice.

Now the god spoke again.

“Why not? It has flesh and blood like any other animal. It will sustain you.”

“Have you ever tried to eat a monkey?” Vikkel asked incredulously. He was too loud—at least too loud for a hunter. The silver monkey noticed the small boy, bared his golden teeth at him, and disappeared into the canopy of leaves.

“There goes our dinner,” the god sighed.

“Well, that wasn’t our dinner. I don’t know what you eat at the Halls, but, down here, we don’t eat monkeys.”

His god snorted. Snorted! Was that a behaviour befitting a celestial being? This was one of the reasons why Vikkel didn’t like Avuktha. He was too casual, too relaxed. It was almost like having an irritating elder brother who had brought embarrassment to the family. Vikkel had trouble accepting that he had almost died and came back to life for this. THIS!

He resumed his stealthy walk, going deeper into the forest. It was dark and damp in the heart of Hoarwood. Rarely could sunlight pierce through the thick canopy of leaves and branches above. It was also cooler here, with soft breezes blowing from the north that made Vikkel shiver. He wasn’t wearing anything warm. He didn’t think he would have to come this deep.

“What is this place?” his god asked. His god asked a lot of mundane stuff instead of keeping his mouth shut. “Why is it so cold here?”

“Witches’ curse,” Vikkel answered tersely. He expanded his godmind. “See anything?”

“Squirrels. Worms. A lot of glowing mushrooms.”

Vikkel sniffed.

“Hey, it’s not my fault that there’s nothing here,” Avuktha sneered in his mind. “And it’s not my fault you are a terrible hunter.”

Vikkel didn’t burst out in anger. It was a difficult feat—very difficult. He could feel his godmind moving hither and thither, tugging at his heart. He pulled Avuktha closer, shortening the leash of his godmind.

“Just stay close to me,” he said without opening his mouth.

“Humph.” His god didn’t sound so pleased. But he didn’t argue, not in this regard. For what else are gods but slaves to the human?

***

At the southern edge of Hoarwood, there was a glade, lush, radiant, and small. In the middle of that glade stood an ancient, eroded idol. Mudda had said it was an idol worshiped by the giants, back when the witches had ruled this region, back when the world was still alive. Vikkel stared at the figurine, transfixed by its glistening surface. No one in the village could tell what the shape was supposed to represent, with its mass of tentacles, eyes, and chitinous armours. Vikkel’s father had said it was the true shape of a witch. The priests had said it was the catalyst that started the Ragnarok. No one knew for sure. And thus the idol stood there alone in that glad, with no worshippers to smear sindoor on its surface. It looked lonely.

“Raatri Maate, sahasra pranamam,” his god whispered.

“What did you say?” Vikkel asked.

His god didn’t answer. The grass at his feet whispered, waving at the open blue sky. Vikkel shivered again, but not from the cold. He felt uneasy and glanced around. Trees loomed around the glade, their dark leaves rustling in the wind. Something howled in the distance.

“Got the shivers, heh?” asked his god mockingly.

“Shut up,” Vikkel spoke aloud, but his voice cracked. Feeling uneasy here was absurd. He’d been hunting in these parts of the woods even before he’d learned how to walk properly. He knew Hoarwood as it knew him: intimately. This discomfort he was feeling had to be nothing but anxiety. This was the first time he had come to the woods alone, armed with nothing but a spear. In a way, this was an unofficial after-ceremony to prove he was a true grownup. Villagers were bound to expect big things from him, especially after what Mudda had pulled off two years before.

Mudda, Vikkel’s elder sister, was about three years older than him. After her awakening ceremony, which had allowed her to form a godmind with Ahuta the Furious, she had gone into the woods and came back, draped in the fur of a hellwolf. Vikkel remembered burying his nose in that soft and supple white fur, breathing in the musty smell of filth, rot, and blood. That night, as he lay under the fur along with Mudda and their father, he had quietly promised himself to hunt something as glorious as a hellwolf. Maybe a windman, maybe a dragon.

“Dragon?” scoffed at his god at present. “You, a green snotty boy, hunting a dragon?”

“Can you not slip inside my mind?” Vikkel grunted. He gave the idol a wide berth. “It’s rude.”

“Can’t help it,” Avuktha sniffed. “There I was, happily feasting in the halls with my brethren, oblivious to your mundane problems. Now, I’m down here, forced to see your naive fantasies, forced to listen to your whine. So the most you can do for me is to hear me complain about it.”

Vikkel didn’t argue. He had reached the opposite side of the glade. Sentinel trees towered before him, creating a seemingly solid wall of lichen-encrusted trunks, sharp finger-like branches, and thick violet leaves.

“You can’t be serious,” his god droned on. “Dragons are dangerous, lad.”

“You are so wise.”

“Don’t you check me like that,” Avuktha flared up inside his mind. “I don’t know what your backwater priests have told you, but dragons are not something you hunt with a wooden spear.”

Vikkel didn’t answer. He slipped between the trees. Darkness. It took him some moments to get his vision back. He blinked and pushed on. On this side, the forest was denser, darker, and older. Vikkel had been to these northern parts several times, but always with a hunting party. This was where his sister had killed the hellwolf, piercing its head with nothing but a wooden spear, like the one he was carrying right now.

“I doubt there are any dragons left anyway,” his god chimed in. “There is none here in this place, that’s for sure.”

“How do you know?”

“Well, for starters, I was there during the sundering.”

Vikkel trembled; he couldn’t help it. At the womb of this primordial forest, no one would like to think about the final battle of the gods, when the sky had split open and darkness had seeped out of the earth like water. The world died that day, and since then the corpse of it has only become colder and colder.

“You were there?” Vikkel asked, his tone doubtful.

“Of course I was. Everyone was there. Everyone had to participate. It was required of us.”

“Why?” Vikkel asked. He knew why, but he wanted a god to say it.

“To destroy the world, of course. Plunge it in blood and chaos and death. To topple all civilizations and break the hubris of all mortals. That is how everything can be reborn, pure and untainted by sins. The cycle must continue.”

Avuktha paused.

“I still remember the blood-red sky,” he continued as his host moved deeper and deeper into the forest. “I was a lowly soldier, part of the vanguard, armed with nothing but golden armour and a spear made of light. I remember the booming sound of Hasthina, telling us to stand resolute.”

Vikkel listened quietly, drinking every word. It was one of those rare moments when he was glad to be awakened.

“I was scared. It was supposed to be a battle where many of us had to die. The balance demanded so. So I was scared—terrified. I held my spear so tightly that I could see the shape of my bones through my knuckle. That was when I saw the dragons.”

A twig snapped. Avuktha stopped talking. Vikkel slowly expanded his godmind, urging his god to look around. He held his spear poised towards a bush from where the sound had come.

“It’s a deer,” his god whispered after a few heartbeats. Vikkel crouched and started to walk in a circle, keeping the bush at his center of vision. He took his steps very softly, careful not to step on anything dry. The trees watched.

It was indeed a deer. Well, more of a fawn, really, with antlers barely pushing through its skull. It was pulling at some flowers with its teeth in a careless manner that bespoke its lack of survival instincts. The wind was at Vikkel’s side, blowing away from the fawn. The herbivore was there, ready for the plucking.

Vikkel hesitated.

“What are you waiting for?” his god whispered in his mind. “Throw your spear and let’s go home. There is a faint smell in the air here that I do not like.”

Vikkel didn’t answer. His god wouldn’t understand. He couldn’t just kill this meager animal on his first true hunt. Well, if he was someone else, maybe it wouldn’t have mattered. People had come back with worse things on their first hunts: rabbits, frostbirds, and squirrels. Hell, people still made fun of Bragga for coming back with a small rodent still half alive and squirming in her hands. Vikkel doubted anyone would say anything if he came back with that fawn slung over his shoulder. People wouldn’t be too impressed, but they would not think of mocking him either. But he just couldn’t do that; it would be the easy way out. He had to prove himself to the villagers that he was something more than just Mudda’s scrawny little brother. He had to prove himself to his sister.

“Are you serious?” his god asked exasperatedly. “Nobody cares for this hunt except for you, alright? What is this barbaric ritual anyway? Why do you need to kill innocent animals to prove your adulthood?”

Vikkel was silent. He stared at the oblivious fawn, still feeling uncertain.

“Just throw the damn spear,” his god hissed and pulled at his heart so hard that he almost stumbled forward. He placed his left foot before him to regain his balance and accidentally stepped on some dry twigs.

SNAP!

The fawn looked up uneasy. It had noticed its hunter. One heartbeat later, it began to hop away from Vikkel, scattering rotten foliage, twigs, and brown leaves.

“THROW IT NOW!” Vikkel’s god screamed so loudly that he winced. But the creature was gone, lost amongst hundreds of trees. Somewhere far above, a raven cried out. The trees still watched; they still listened.

“YOU STUPID ARROGANT BOY,” Avuktha’s anger crashed against Vikkel’s psyche. “YOU FOOL, YOU—”

Avuktha’s angry rant was cut off. Vikkel had smothered his godmind. The tugging sensation in his heart vanished. His awareness diminished. It was like getting choked by an invisible cloth. His vision dimmed, and the forest became darker, more sinister. His hearing felt muffled; all the scurrying, slithering, thumping, and tapping sounds of the hidden lives faded away to nothing. His nose felt clogged up; the sharp undergrowth stench became nothing but a faint earthy smell.

Vikkel sighed. It would be a lot harder to hunt without his godmind, but it could be done. He used to do it when he’d come with Mudda. But then again, it was Mudda who had led him to most of the animals, and it was Mudda who had taught him how to throw a spear. Vikkel shook his head. No! He could do it. He would do it. He didn’t need a god to hunt something in these woods.

***

An hour later, Vikkel cursed himself. He had ventured deeper into the forest, deeper than he had gone before in his life. Yet he had not found anything as marvellous as a hellwolf. A small lizard, some land crabs, a sloth bear, and a half-eaten carcass of a rabbit. It was as if the forest was mocking him, almost punishing him for letting that fawn getaway.

He sat under a dead tree, its black trunk dappled with green lichen, and wetted his parched throat. He shook his waterskin and heard a hollow slosh inside. His water was almost gone. One of the first things that Mudda had taught him was to never drink any water from the woods.

“On the second day after their deaths, the witches cursed the water of the woods,” his sister would say. “Any man who drank from brooks, bogs, pools, or ponds just curled inward and died bleeding. So goes the story. Always bring enough water when you come to hunt.”

Vikkel had not brought enough water for this hunting. He still felt thirsty, but he was afraid to take another swig. Over his head, the leaves rustled ominously; it sounded almost like the hissing of a thousand serpents. The forest felt cold now. Goosebumps formed on his skin with every gust of wind. It was getting late. He could not see the sun through the dense canopy over his head, but he could feel it in his bones. Soon, night shadows would gather in the woods, and curling mists would seep out of the earth. He needed to finish this as quickly as possible. He had no other choice.

He tapped his godmind.

A flash of headache, but only for a moment. It was followed by a tugging sensation as if something was physically pulling at his heart. And then, the forest suddenly came alive. His vision flared, and the surroundings became less shadowy. The smell of rotten foliage hit him like a solid wall, and he suppressed his gag. The silence melted away.

That was exactly when Vikkel realised something was watching him. Ahead of him, hiding in a shadow that even his enhanced sights could not pierce. But he could hear it though, whatever it was. He could hear its uneven breathing, pulsing against his eardrums.

What was that? Vikkel gripped his spear tightly. He could see a few pine trees crowded together like gossiping wives. Darkness reigned at their feet, obscuring everything around them. Something was peeking at him from behind the trees—something that loved him not.

“Avuktha,” he said in his mind. “What is that?”

Silence.

“Are you there?”

Silence.

“Look, you can be grouchy when we get back to the village, but right now I need your help.”

Silence.

“Do you want me to die here? Far away from everyone else? If the wolves find us, then no one will even find our corpse.”

Now he could feel his god hesitate, for the tugging sensation in his heart amplified a little. Without a proper cremation performed by the priests, gods would remain trapped within the corpses of their hosts. It would mean terrible imprisonment, for the gods couldn’t communicate with other human beings. They would have to cling to the rotting carcasses of their masters until someone found them and went through the proper rituals. The priests had told Vikkel terrible tales, of gods clinging to the remains of their hosts for centuries, of gods going insane, and finally cannibalising the tether that kept them tugged to their hosts, of gods wiped away from existence.

Avuktha didn’t like to think about it.

“Where are we?” he finally asked.

“I don’t know, somewhere in the north.”

“And you still haven’t found anything to kill, huh?”

“Look, can we talk about this later? There’s something weird watching us right now, and I’ll feel a lot better if you can just tell me what it is.”

Silence.

Vikkel sighed. He forgot how moody his god was. He was about to stand up and look into the matter himself when his god spoke again.

“Broaden your godmind.”

Vikkel gladly complied. He felt his heart tighten as his god moved farther and farther away from him. Vikkel slowly but deliberately stood up, his spear poised at the beast. He waited.

The woods had gone unusually quiet. Even with his godmind, all Vikkel could hear was the uneven breathing sound of the beast.

Then suddenly, his god snapped back to him.

“Run.”

“What?”

“Just run.”

As if in answer to his god’s panic, something rustled in the bushes behind the pine trees.

“What is that?”

Something burst out in the open, pushing the pine trees apart. Something large and furry and monstrous. With two leaps, it closed upon the boy, standing only a few feet away.

It was a hellwolf.

Three blood-red eyes stared at Vikkel. Two large horns curled over those eyes. Rows and rows of teeth bared like a leer. The hellwolf was midnight black, its fur matted with filth.

Vikkel froze. The monster towered over him like a nightmare, emanating a stench that was even more overwhelming than the rotten foliage.

How did you fight something like that? A being with such an awesome presence, its muscles pushing against its dirty fur, its teeth larger than his spear’s tip, its nails as large as knives. How had Mudda killed something nightmarish with only a wooden spear? The hellwolf hadn’t moved. It watched him, its growls deep like thunderstorms. It was almost like the beast was trying to scare him off. Why wasn’t it attacking?

“There are three cubs, just behind the trees,” Avuktha answered his questions. “The bitch doesn’t want to attack you, but it will if it feels you are a danger to her cubs.”

Vikkel hadn’t moved an inch since the hellwolf had burst out in the open. He kept the spear pointed at her, his hands steady as a rock.

“We need to go away,” his god said. “Let it go. How can you fight something like that? It’s madness.”

“It’s fur is black,” mused Vikkel. “Opposite of the white fur we had back at home.”

“Don’t say it. Don’t you dare-“

“Maybe the Gagganam Halls willed this encounter.”

“Now you are just trying to make connections where there are none,” Avuktha flared inside his mind. “Here’s the truth, boy. The gods do not care about this world, and they certainly don’t care about you and your hunt. The priests, your neighbours, your family—no one cares about what you hunt today. We need to go.”

The hellwolf moved forward and snapped its jaws. Vikkel winced but held his ground.

He could feel his god tugging at his heart, trying to move away from the hellwolf. He retracted his godmind, pulling Avuktha closer.

“Can you Manifest yourself?” Vikkel asked quietly

Avuktha laughed like a maniac.

“Can or can you not?” Vikkel asked impatiently. His sister had managed to kill the hellwolf without any manifestation, but he guessed he wouldn’t mind if his god physically aided him in defeating the monster.

“No,” his god sounded monotonous. “We are still not of one mind.”

Then his god went silent. Vikkel nudged at him but found him unresponsive. He turned off his godmind.

The forest watched quietly, waiting to see if the scrawny little boy would run away or stay and fight. Birds cried, chirped, and sang as they flew back to their nests. The sky was alive with moving figures. True darkness had begun to gather. Soon the mists would come.

Vikkel thought about his sister, so fierce, so carefree, so powerful. When she manifested her god, she looked like a goddess herself, wreathed in an inferno, a glowing sword in her hand. He closed his eyes and thought about how the villagers would gasp when he’d come back to them wreathed in midnight black fur and how his father’s eyes would warm up.

Maybe then Father wouldn’t feel embarrassed by his sickly son, always so shy and demure, always scared of the night. Maybe then Father would not whisper to Mudda, “I wish Vikkel were more like you,” while Vikkel pretended to sleep. Maybe then…

He opened his eyes. The hellwolf was waiting. He had made up his mind.

He leaped with the spear in his hand, unaided by his godmind.

***

The forest was alive with dots of light. If a raven had flown over the trees, it would have recognised them as fires. If it had swooped down and sat on a branch, it would have seen people, their faces pale because of the torchlight they carried. If it had waited for a little bit, it would have seen a girl wearing a cloak made of white fur.

Mudda walked with half of the village, calling out Vikkel’s name. She could feel her god tugging at her heart as he moved around, looking under the shrubs and undergrowth. She had been crying before, and now tears stained her face. She hadn’t wiped them away. Mists swirled around her feet, curling away whenever it got too close to the flame.

“VIKKEL,” she screamed for the umpteenth time. “VIKKEL, WHERE ARE YOU?”

And the tears came again.

It wouldn’t be until dawn that she would find her brother’s corpse, his body ravished by ferocious claws. She wouldn’t cry then, she wouldn’t wail. She would just cover her brother’s body with the white cloak. She wouldn’t think about how years ago she had found the white hellwolf, already dead and full of worms, and how she had just skinned its fur and returned to her village.

Tags: English Section, Trinamoy Das, নবম বর্ষ প্রথম সংখ্যা