Cosmic Horror: The Scariest Subgenre

লেখক: Soumyajit Kushari

শিল্পী:

“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.” – H.P. Lovecraft

One cannot discuss H.P. Lovecraft and cosmic horror without showcasing this excerpt from his seminal work, “The Call of Cthulhu” (1926). It is a monologue that doesn’t hold anything back and lays out all the cards that cosmic horror holds. At its core, this is exactly what cosmic horror is all about. It imagines a world where not all knowledge is meant to be learned, and as we dig deeper and get closer to ancient truths, we inevitably spell our doom.

Human insignificance in Cosmic Horror

Lovecraft’s works and cosmic horror as a whole have, at their core, a very cynical outlook on the nature of reality and the position of humans in it. In cosmic horror, humans and humanity at large are as insignificant as a speck of dust. Lovecraft has a penchant for describing humanity throughout much of his work:

“…the miserable denizens of a wretched little flyspeck on the back door of a microscopic universe.”

And really, this goes to add to the unsettling and dread-inducing nature of Cosmic horror. Humans have a strong need to feel significant, to feel that their lives have meaning. For many people, coming to terms with the fact that our intelligence and emotional complexity arise from a measly 4% difference in our DNA compared to a chimpanzee’s DNA, proves to be too much, and they’d rather not think about it or reject the scientific evidence and believe alternative theories that can make them feel more special. In one of Lovecraft’s most recognized and acclaimed works, At the Mountains of Madness (1931), a scientific expedition to the Antarctic uncovers an ancient city that predates humanity by many thousands of years, maybe more. As the story progresses, the expedition finds ancient creatures, creatures that once inhabited this city, stuck in the ice, creatures they start referring to as the “old ones.” These beings were described as:

“Six feet end to end, three and five-tenths feet central diameter, tapering to one foot at each end. Like a barrel with five bulging ridges in place of staves. Lateral breakages, as of thinnish stalks, are at the equator in the middle of these ridges. In furrows between ridges are curious growths—combs or wings that fold up and spread out like fans … which gives almost a seven-foot wing spread.”

As the story progresses, through hieroglyphics on the city walls, the expedition members discover that these were advanced creatures and engineered another species, a species to serve them. It is implied in the story that all modern life on Earth evolved from the residual biological matter of these servant creatures. This already goes to show how inconsequential humanity is in this story. But that’s not all; in the hieroglyphics, there are whispers of another creature, one feared by even the elder beings, and as the last two survivors of the doomed expedition make their escape, one of them makes the mistake of looking back at the receding Mountains of Madness:

“All that Danforth has ever hinted is that the final horror was a mirage. It was not, he declares, anything connected with the cubes and caves of echoing, vaporous, wormily honeycombed mountains of madness which we crossed; but a single fantastic, daemoniac glimpse, among the churning zenith-clouds, of what lay back of those other violet westward mountains which the Old Ones had shunned and feared.”

He saw a creature (if we can even call it that) that even the old ones feared—the old ones that engineered a species to serve them; a species whose residues gave birth to all life on earth. When creatures like this exist, humanity becomes nothing more than a speck of dust.

The Philosophy of Cosmic Horror

Lovecraft’s stories had embedded the literary philosophy known as “cosmicism.” Lovecraft developed cosmicism by taking elements from philosophies like existentialism, nihilism, and absurdism. The three of these are very closely related because at their cores, all three posit that human life has no inherent meaning. Lovecraft’s universe is cold and indifferent to human struggles. The existentialist’s isolation and search for meaning is mirrored in how Lovecraft’s characters battle insanity on a journey to forbidden knowledge and revelations beyond comprehension. Lovecraft’s tales are rife with nihilism because the setting is a chilly, heartless, and uncaring universe that declares human ideals and efforts to be ultimately pointless. You can see the influence of absurdism in the sheer helplessness and borderline lack of free will of Lovecraft’s protagonists in a manner that harkens back to the myth of Sisyphus. Cosmicism merges these philosophical threads, underscoring the helplessness and existential dread that result from the encounter with an incomprehensible, indifferent cosmos. Lovecraft once said

“Contrary to what you may assume, I am not a pessimist but an indifferentist—that is, I don’t make the mistake of thinking that the… cosmos… gives a damn one way or the other about the especial wants and ultimate welfare of mosquitoes, rats, lice, dogs, men, horses, pterodactyls, trees, fungi, dodos, or other forms of biological energy.”

And so, in cosmic horror, humanity has the same significance as mosquitoes, rats, lice, dogs, horses, pterodactyls, trees, fungi, dodos, and so on. Our protagonists aren’t active but passive, and we as readers helplessly watch as things keep happening to them that they have no control over.

Capturing the Ineffable

The ineffable is defined as too great or extreme to be expressed or described in words. It lies at the very core of all cosmic horror; cosmic horror is the horror of coming face to face with the ineffable, be it an entity beyond comprehension, such as the elder beings, or be it a spatial anomaly that acts as a portal to a different dimension, as seen in “Dreams in the Witch House”(1933):

“As time wore along, his absorption in the irregular wall and ceiling of his room increased; for he began to read into the odd angles a mathematical significance that seemed to offer vague clues regarding their purpose. Old Keziah, he reflected, might have had excellent reasons for living in a room with peculiar angles; after all, was it not through certain angles that she claimed to have gone outside the boundaries of the world of space we know? His interest gradually veered away from the unplumbed voids beyond the slanting surfaces since it now appeared that the purpose of those surfaces concerned the side he was already on.”

Or the corruption of an environment in ineffable ways by a foreign object, as seen in “The Color Out of Space”(1927):

“It was just a color out of space—a frightful messenger from unformed realms of infinity beyond all Nature as we know it; from realms whose mere existence stuns the brain and numbs us with the black extra-cosmic gulfs it throws open before our frenzied eyes.”

Describing these things is not an easy task. They are, by definition, indescribable. For something to be ineffable, the very units of reality that make it up must be alien to us. So, how does an artist attempt to capture the terror of confronting something indescribable?

“It was everywhere—a gelatin—a slime; a vapor;—yet it had shapes, a thousand shapes of horror beyond all memory. There were eyes—and a blemish. It was the pit—the maelstrom—the ultimate abomination.”

In the short story, “The Unnamable”(1925) using contradictions and vagueness, artists in the cosmic horror space can convey things (with varying levels of success) that aren’t describable.

Take a look at these colors, they’re from the opposite ends of the color wheel. You can cross your eyes and make them overlap, and what you’re left with is something that is both blue and red but not really a solid color.

Making the mind jump between these contradictory descriptors—slime, vapor—has a similar effect, and the reader gets a small glimpse of something indescribable. Yet, this technique still relies on units of reality we understand; we know what slime is, and what vapor is. That’s the point; even after trying, this is the best description the character can give about this specific entity, a description filled with contradictions. In reality, it’s his impression, and the entity itself is truly indescribable.

This is not what Cthulhu looks like. The painting you are looking at was made from a description that, in the story, was a failed attempt by a cult to describe what Cthulhu looks like. In reality, Cthulhu is truly ineffable. And still, the vagueness through which he is talked about, again using the technique mentioned before, makes him a terrifying entity. This is all well and good, but what’s the point of this exercise? Can we achieve something by straining against the nature of the ineffable and trying to put it into words, even though it can’t be? And I know this is ironic because of what we’ve talked about so far, but is there something more meaningful behind this exercise?

“constant talk about “unnamable” and “unmentionable” things was a very puerile device, quite in keeping with my lowly standing as an author”

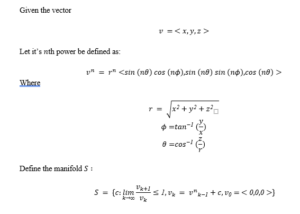

This is also from “The Unnamable.” Lovecraft takes a jab at himself, maybe he felt that the effort of trying to describe the ineffable was misplaced. Arguments can be made that objectively speaking, science is more adept at tackling the issue of describing the ineffable. Take a look at this—

This is from Alex Garland’s Science Fiction horror flick, Annihilation (2018) (which in my opinion is one of the greatest cinematic depictions of cosmic horror ever). Can you try to describe what you are looking at here? Any description would fall short of what it is in actuality. You might not be able to describe it but—

–math can. These are the equations that make that shape. These equations make that shape, it is defined by the manifold . It’s called a Mandelbulb, and it is a kind of hypercomplex fractal. Mathematics is indeed adept at describing it. Another example of it is that you who are in a field related to or have studied STEM subjects must have come across this; just think about it: it is something that is beyond our comprehension, the foundation of “imaginary numbers.” Again, through abstraction, math can get closer to more accurately describing what would be considered ineffable if math were not involved. But this isn’t always the case. And I have found this fascinating since I realized it. At the beginning of Lovecraft’s short story, The Nameless City (1921), a couplet is mentioned:

“That is not dead which can eternal lie, and with strange aeons, even death may die.”

There is a concept in cosmology called the heat death of the universe. As the universe continues to expand, galaxies will gradually drift apart, and stars will exhaust their nuclear fuel, leaving them to fade away into cold, dim remnants. Stellar processes will cease, and new stars will no longer form, resulting in a universe devoid of light and heat-generating processes. As the universe expands, it will also cool down due to the expansion itself, leading to a gradual drop in temperature. Over countless trillions of years, black holes will gradually evaporate through Hawking radiation, releasing the last traces of energy they contain. As this happens, even the most massive and energetic objects in the universe will eventually disappear, leaving behind only photons and particles scattered across vast, empty spaces.

As the universe keeps expanding, any remnant matter will be ripped apart into elementary particles. These particles will be uniformly spread out, and the temperature will approach absolute zero. Then, one day, the entropy of the universe will reach its maximum and stop changing. With no change in entropy, the concept of time itself is rendered meaningless. The universe goes into a permanent state of inactivity.

That is not dead which can eternal lie.

We can’t really say that the universe is dead, more so that it goes into eternal slumber. The particles that made up everything that ever was are still here, but disjointed. The universe sleeps in this cold and stagnant form for all eternity.

And with strange aeons, even death may die.

As entropy becomes constant, time dies, and as a consequence, death, a manifestation of time, also dies.

The universe becomes a dark, cold, empty, stagnant void. Nothing will ever be created, and nothing will ever be destroyed.

These two lines were written in 1921, much before the popularization of this concept in our culture. It is true that Lovecraft was very well versed with the sciences but understanding a concept such as this with this deep an appreciation of its details (that he was able to so succinctly and poetically capture it) seems unlikely given his troubled life and incomplete education. It might be reasonable to assume that he only wrote them because they sounded cool and felt foreboding. He wrote them in trying to make you feel the ineffable, and in this instance, art reached a truth that science reached after hundreds of years of progress.

Herein lies one of the most unsettling aspects of cosmic horror. Even though it is fiction, its reliance on logic and science makes it more real than one would expect. It isn’t all that crazy to think that perhaps there are a lot of things that humanity at large should not know.

We Need to Know or We Shouldn’t Know

We shouldn’t know because we can’t know. After all, to us, these things are truly ineffable. Perhaps straining in trying to know these things might indeed lead to the outcome Lovecraft hinted at in Call of Cthulhu “…that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

Tags: English Section, Soumyajit Kushari, নবম বর্ষ প্রথম সংখ্যা