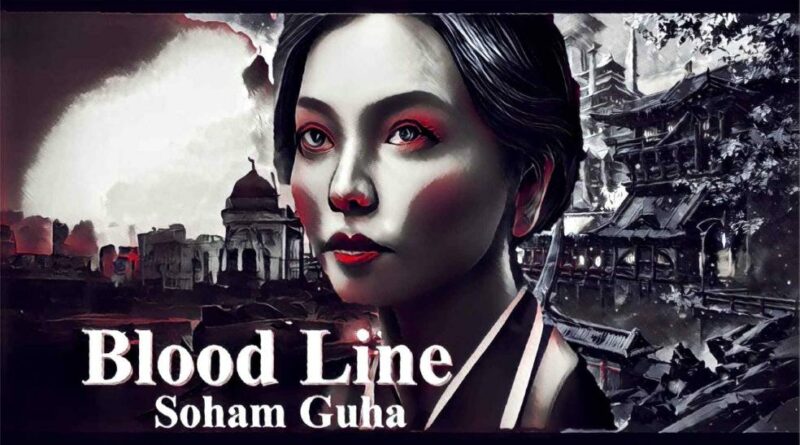

Blood Lines

লেখক: Soham Guha

শিল্পী: Team Kalpabiswa

The night is coming to a city wrapped in fear of war. The sirens scream, telling me it is time to hide. I hurriedly closed my shop and placed a small curse on the rune-lock. Thieves are prospering, using these blackouts as their cloak. If someone chooses to break the lock, he shall suffer from a sudden outburst of explosive diarrhea. That will deter the malevolent parties for the time being.

I watched for the wandering eyes and wink at the beggar sitting on the opposite side of this narrow Bazar Road. He keeps an eye on my shop in exchange for an anna or two, and I can sleep at night with relative peace. Despite the ersatz appearance, my shop has become a site of attraction, particularly to the troops from the faraway lands. Not because I sell ginseng at the cheapest rate in the entire Calcutta, not because I sell untraceable opium, but because of my reputation as a healer. They say I can even mend heartbreaks. That is an overstatement. My magic, my sole inheritance, can only heal physical trauma.

Second World War brought me some very exotic customers.

“Here, Sadhon Miya,” I toss a coin to the beggar, “Take care of yourself.” I glance at the overcast sky, queer for a winter month. “It will rain tonight.”

He nods slowly, blinking his ghostly reddened eyes. I know he will spend the lion’s share of this bestowment tomorrow, as soon as I open my shop, to buy opium. He thinks I am generous; I see him as a loyal investment who often brings friends.

It is only six-thirty in the evening, and the entire city is silent as death. Except for me and the pack of street dogs that follow me home in pursual of the biscuits I throw at them, there is not a soul present.

There are roars above me. I cannot distinguish if those are sounds of thunder or the screams of the metal birds. People are scant except some scattered souls who call the pavements their home. Erecting one gunny shed overhead, a woman is cooking khichri in a small pot. There is more water than rice and dal. The burning cow-dung cakes in the oven give her sleeping child a faint glow and some warmth. She looks up, hearing my familiar footsteps.

“You should stop, Sankar Babu,” she says. Her tongue sharp like an iron blade. “You have already done enough. GO AWAY.” The child wakes up to her jagged approach.

I look at the crying infant. Her eyes are like mine, dark with a hint of green. One day, he will be helpful. Her mother used to be a tenant in the Sonargachi red-light district, and I was her regular customer. And I am the reason she was thrown out of that facility. The ruthless ring of prostitution seldom has a place for pregnant women.

I crouch before her and fish out a bundle of notes. “Take this, please. You need this.”

Her jaw clenches. “I am not a damsel in distress, Babu, nor your disposal deposition box for salvation.”

I raise my hand to place it on her shoulder but immediately shove it down. The last thing she needs is inorganic consolation. “I am not doing this for you,” I say. “This is for him.”

The conversation soon becomes a quarrel, and when I leave, she is still screaming and cursing behind me. But she keeps the money. I find comfort deep inside my heart. As if a flower is blooming again on snow after an eon of blizzards. Shangri-La was always a place of legends. After Hitler raided our Tibetan monastery and forced my sisters and brothers to sit before the pointed machineguns, outcasts like me became the sole survivors. Now it is only wreckage, full of charred bones and scorched scrolls.

At late night, sounds of trumpeting thunder tore away my sleep. I rub my eyes and rush towards the veranda. The southern horizon is glowing. The Axis airstrike has decimated Fort William. I know when the doctors fail to play against Yama, the officers will call for me. Tomorrow will be a good day for business. When young pawns fall in an older men’s war, on the blood-soaked ground, between torn limbs and smoke, the parents’ cries are like distant stars in the tranquility of death. War glorifies heroes; it never talks about lost souls.

I realize if I had practiced the dark arts more, if I knew all the delicate processes of necromancy, I would have been a millionaire. But when I realized profiting from one’s loss was against my conscience, I was already banished.

Calcutta stays awake for the rest of the night, but no one dares to query. The rain at dawn finally subsides the raging fire.

When I reached my shop in the morning, I found the Bazar bustling as usual, as if nothing had happened the night before. Even Sadhon Miya is eagerly waiting for his daily dose of opium. At a distance, I notice two women waiting for me as well. One is nearly sixty, judging from her pepper-salt hair, though there are few wrinkles on her face. The other sits on a heap of loose bricks, leaning her back against the wall. Her face is paper-white. From their shared resemblance, I realize they are mother and daughter.

Just as I unshackle my untampered lock, the older woman comes rushing. She almost shoves Shadhon Miya aside. “Ojha sahib, help me. My Avanti,” she points at her pale daughter, “She’s dying.”

I say coldly, “Miss—”

“Sharmila Nayek,” she says.

“Ms. Nayek, I’m afraid you have come to the wrong place. You should see a doctor.”

“I have! And that man, oh that man, after swallowing a handsome heap of money, says he cannot do a thing for my daughter. ‘Says I should pray now. How can a mother pray to God who has left us in such a perilous time? How can a mother witness her only child’s death? Please, Ojha sahib, I have heard about your miracles. They saw you can even rise dead. Look at my girl. Is she beyond saving?”

For the first time, I study the patient. Despite her malnutritional state, the bloodlessness of her cheeks, or the distantness in her eyes, I see she once was a beautiful maiden. “What happened to her?” I ask.

“Leukemia,” she says with a large gulp. The queen of all maladies. “She works – worked – as a morgue assistant in the Medical College. The hours are always laborious and exhausting, especially since they moved the Front to East India.”

Collateral damage in a fruitless war for our colonial masters. I often speculate about the Bengali man raising an army in Singapore and how right he is. Drugs of cancer, or any drug, are scarce and can be found only at an extravagant price. People were illegally hoarding foodgrains, driving the price up of everything else even more. If this continues, there will soon be a famine. When corpses are making mounds, it is difficult to recuperate from personal losses. There are no sympathizing shoulders.

I see Sadhon Miya glaring at Ms. Nayak from a distance. But when she stares back at him, he steps back. And he swallows his anger. I expect a confrontation, but the man retreats with slang under his slurry tongue. I rummage through my stash to see if I still have some Swarnoparni leaf dust left. The extinct shrub of golden leaves that grew on the foothills of Shivalik Himalaya is the only cure. However, no one had seen a single living plant in the wild for at least five hundred years. The last sapling was with Atish Dipankara that he planted in the gardens of Shangri-La.

I smuggled a few leaves when I fled.

“It will cost you a fortune,” I say while searching. My peripheral vision quietly observes the oddity in this shantytown Bazar, a Chevrolet 1936 model. Like a preying hawk, the way the driver is watching us, I soon fathom who the owner is. I also notice their garments. Expensive Jamdani sarees. No wonder they can afford a doctor these days. They indeed belong to some aristocrat household, or someone who has immensely profited from the turmoil of war.

“Call any price, Ojha sahib,” she mutters and shows me a fat bunch of hundred-rupee bills, more than the price of that car. It is more than I earn in a year. Now it is my time to swallow my greedy saliva.

To my dismay, the pouch was empty. What now? I ask myself. I cannot let this party return empty-handed. I can perform healing magic, but that will hardly be sufficient. Besides, treating a disease tormenting her entire body will drain my chakra reserve, even thrash me into a coma. Is that worth all that money?

Then, I remember.

When Atish Dipankar went to Shangri-La, he had his eldest disciple, Nayratna Bidyavushan, with him. Both were monks at Vikramshila Maha Vihara, and inseparable friends since childhood. He was my great-great-grandfather.

My first memory is of the sky that shined above the architecture of Gandhara style through a circular mouth of rocks. Hidden between two ramming glaciers, this secret valley was home to the sacred arts of Vajrayana Buddhism. As Bakhtiyar Khalji continued to destroy universities and viharas, all the surviving scrolls were transported to this last frontier. Hidden in the cradle of Tubo, the monks spent generations to restore the knowledge lost to anarchy and the flow of time. Until the Third Reich came with their helicopters, hoisting our sigil of peace as their crimson, pearl, and charcoal flag of oppression. Shangri-La was sacrificed in the flames of the Ubermensch program.

I spent my early years studying the meaning of life and death, a discipline that originated from the mouths of the bodhisattvas. I studied Ayurveda and chakra manipulation. Every child born in Sangri-la was treated with various herbs – found only in the deep cradles of Himalaya – and forgotten medicines. Isolated from the rest of the world, imbuing these sacred nectars of ancient forests in our blood gifted us the ability of regeneration and long life. We learned how to control our charka cores and use them to heal those in need. Save from some weary, lost travelers and nomadic herders, few knew about the gifts we possessed.

Our blood is the key.

I turn to Sharmila. “Escort her to your car and lay her down.” I grab the siphoning tube and a syringe. Seeing her bewildered eyes, I add, “I observe my surroundings.”

If I were any other individual in this sprawling city, I would worry about the blood groups recently distinguished by Landsteiner. However, my isolated upbringing turned me into a universal donor. It is not my blood, but the strange microscopic organisms floating in it make the transfusion possible. Those things are always hungry for compatibility checks, always seeking a new host.

As soon as the crimson fluid reaches her system through the transparent tube, a faint trace of redness returns to her cheek. Her lips gather color and her gasps become breaths. A minute later, I disconnect the tube and wipe the sweat from my forehead.

“She will be well,” I say. Here I am huffing. My legs are weak. But I feel a glint of satisfaction. I performed the most blasphemous act prescribed in our codes—another spittle on my father’s ashes.

Even after the car drove away, engulfing my nostrils with thick smoke, Avanti’s soft “Thank you” resonates in my mind. In my pocket, the bundle of worn-out notes makes a boasting lump. The army car comes soon, as anticipated. The sergeant hands me an official letter. I do not ask him about the casualties, nor do I gloss over the sum payable. Before boarding the car with a bag full of herbs and healing potion, I secretly put the opium pouch in Sadhon Miya’s hand. Towards his blissful face, I whisper, “On the house.”

Sadhon Miya stays silent for an awful time. Finally, I hear him yell behind the car. I see him hoisting both his hands in joy, “We are all mayflies in the crossfire, Sahib. Always look for the trenches.”

I recall Sadhon Miya’s daydreaming tales of him serving in Mesopotamia with Kazi Nazrul Islam. Perhaps there is some truth in all his tall tales. I have seen how war changes people, forcing children to become momentary adults and perish in bullet rains and bombardment storms. It is astonishing and depressing to witness our capability of exerting carnage.

I spent the rest of my day, and the day after, taking care of the critically wounded. Most of them, laying still on their beds, doused in morphine, are barely adults. There is little facial hair on their faces. Yet, whenever I force them to swallow the potions, adverting the cynical looks of the certified doctors, I see little trace of innocence in their muted eyes.

Some of them will not walk anymore; some will eat with the help of others; some will see only the darkness of the world, for I cannot pull out the shrapnel embedded in their eyes. But all of them will live. Deep down, my father smiles at me and thanks me for using my gift for the betterment of others.

I grind my teeth. How can I forget his fuming face when he threw me out of Shangri-La into a roaring blizzard and told me to find my stakes in the lands of my ancestors? When I reached a Sherpa village after eight days, I could see my ribcage. I still look at my missing toes, claimed by frostbite, and think about my journey. I am a monk without a home.

On the third day, I emerge from the makeshift hospital tent erected beside the bombarded fortress and look at the ghostly sun hiding behind the scattered clouds of a December day. The sergeant drops me at my shop and hands me a small token. He whispers about the ships carrying the wheat and rice of Bengal to the front. He whispers about the coming famine that I already speculated. He clasps my hand and thanks me for saving his brothers. It is hard for me to distinguish the individuals among a hundred wounded soldiers. But I nod and accept the gold coins that once belonged in the treasury of the sultan of Brunei. And I find Sadhon Miya anxiously waiting for me. His posture exhibits all signs of opium starvation. When I open my shop and give him the intoxicating agent, he provides me the coins and a sealed envelope.

“That wretched woman told me to deliver this,” he says.

The letter, though it bears the signature of Sharmila Nayek, is written by a young hand. I smell the soft fragrance she left on the page. The heartfelt gratitude warms my heart battered by witnessing suffering soldiers.

Accepting the invitation, I knocked on their front door the very next day. Sharmila’s house is in Shyambazzar, one of the rich and ancient neighborhoods of that area. The house is old and often repaired. Because of the war, the outside wall is colored gray. Yet, glimpsing at the interior vibrance seeping through the open windows and the Chevrolet sleeping in the car-veranda, I know I am at the right place.

Sharmila welcomes me with a manufactured smile as if she did not expect me so soon. A Kashmiri carpet covers her drawing-room floor. There is a painting adorning the east wall. I forcefully remove my gawking eyes from the renaissance painting of a nude Greek goddess. I blush and wonder if the painting is a replica or the original. Before I conclude or ask the owner about her ultra-modern taste, Avanti enters the room with a plate full of snacks and a fuming cup of Darjeeling tea.

She sits beside her mother, and Sharmila says, “Ojha sahib, I went to your shop, but you were away for duty. So, I hope you pardon the intrusive way of delivering the letter.”

“Please, call me Shankar,” I comment and sip the tea silently. I do not know what I am doing here. I came here answering the call of my dried heart. My transfusion did the impossible. Then I look at Avanti and see all the colors have returned to her face. Her sunken cheeks, now pinkish, have risen from the abyss of her face, her eyes are two glistening stars, her lips are two newly bloomed petals of a rose. “You look perfect, Avanti,” I comment.

She blushes and darts her eyes away from my gaze. Sharmila says, “After her father died, she’s all I have left. I cannot thank you enough for bringing my baby girl back to me. All this, after I am gone, will be hers. Tell me, Shankar, is there anything I can do for you?”

I do not yell my heart’s desire. I absentmindedly touch my unshaven chin and my puckered face. “You have given me more than I asked, Ms. Nayek.” Then, seeing her sad face, I add, “It took me some time to find your address. Calcutta, with all its serpentine alleys and tricky roads, still eludes me.”

Her brows rise. “You are not from Calcutta?”

I take a piece of salted cashew from the plate and answer, “My ancestors were originally from Bikrampur. It was where I was born and raised. Then they migrated to another place. Now I am again here, in Bengal, tracing my roots. I wish to see the village one day, though I am far from my goal.”

“Then you surely know about Atish Dipankara.”

I chuckle. “I speculate that my forebear and he were the sons of the same soil. That is why I try to identify myself as a Buddhist.”

“Then you must know that I praise myself as an admirer of the Buddhist arts.” She points at a painting hanging on the opposite wall. I am lost for words to compliment the gorgeous portrait of our goddess of knowledge, Devi Prajnaparamita. My eyes stumble upon the metal decoration hanging beneath it. From my point of view, it looks like an SS svastika.

“You should hang it correctly,” I grimace. “Our colonial masters are hysterical about this horrifying depiction of the sacred symbol. They will not understand its true significance but see it as an emblem of evil.”

Sharmila presses her lips. She quickly goes and turns the swastika properly. But I see the spinning fan overhead again put it to its prior stance. She sighs and looks back at me. “I will place this elsewhere, appropriately.” I feel the embracement in her voice. She turns to Avanti. “Dear, why don’t you show Shankar Babu what you know about Calcutta?”

Reluctantly, the daughter nods, and a small fire ignites in my heart.

#

Three months later, Avanti and I sit under a tree at Maidan. Around us, the bombed craters were yet to be filled. At a distance, the masked Victoria Memorial stands like an enormous mountain of dirt.

“The Maidan looks like the face of the moon,” Avanti says. She stealthily slides her fingers between mine and leans on my arms. “What will happen to us, Shankar?”

I am almost a decade older than her, but I am the immature one in the relationship. “The way the Japs are annexing Burma, Formosa, or Sumatra, soon if they are not stopped, Calcutta will not be a city of the Raj.”

She asks, “What do you think about Subhas Chandra Bose?”

It was a conflicting topic that raised numerous debates between loyalists and patriots. As I am none of them, I say, “His methods are truly admirable. However, I don’t believe a country’s independence can be achieved only through war.”

“If America can do it, why not us?” She protests.

“It is because of our multicultural, pluralistic, and fractured heritage, Avanti. The only reason any invaders captured our land, even the Britishers, is because we are a race of divided sons and daughters, so busy in quarreling among ourselves that our myopic vision renders us blind towards the outside threat. Even if you look at the independence movement, you will see that it is very centralized, proliferating in old British presidencies like Calcutta, Bombay, or Madras. The Raj rules us, plunders our resources, exploits our fragmented morals by using our countrymen.”

“Sometimes, it feels as if you see the follies of men as an outside observer, and you are well versed with the history of this subcontinent.” She ponders in her following words. “Those times, I don’t feel like I know you at all.”

I clutch her hand tightly. “There are some buried secrets about my past. And one day, I will tell you, for sure.”

“When?” She presents a beautiful smile. Her slightly crooked teeth make her smile more beautiful. Small depressions appear on her cheeks.

I caress her face with my lingering fingers and kiss her suddenly. To her reddened face, I say, “When you will marry me.”

When anti-aircraft guns are continuously pointed at a baleful sky, and soldiers march at a distance with their hoisted guns, when prices of essential commodities are at an all-time high, our feels out of place. She gazes into my eyes as if she can see my soul. She slowly bobs. “I will have to ask my mother. Don’t come to my house until I reply. She’s a bit… protective and proactive about these matters.”

Of course. A girl like her possibly had a long list of admirers. It is a minor miracle that she is with me. What alternate history would have written had she not visited my shop on that fateful day?

I say, “Parental love is always tough, Avanti, especially when you are the only child,” and I remember my father’s face the day he threw me out of Shangri-La.

It is getting dark. The sun is set beside the newly constructed steel giant called Howrah Bridge. I have to return her home before the curfew. I reminded myself.

As we walk along the tramline behind the Maidan, I told her that she shares her name with a city of the sixteen Mahajanapadas of ancient India. She didn’t reply but grabbed my arm suddenly. Her nails pricked my skin. Before I could ask anything, I also saw the reason for her terror. A man had suddenly appeared before us. The blade of the long knife he held is glistening in the faint sunset glow. I gulped loudly. I had left my trusted kukri at home. Who brings a weapon on a date?

“Give me all you have,” the man screams. There wasn’t a person around to call for help. I recognized his voice. Since I stopped merchandizing opium as a change of heart, the withdrawal has transformed Sadhon Miya into something horrendous.

“Miya, you don’t have to do this.” I softly say, lifting my hand to show my unarmed state.

He recognized me as well. “Oh, look who it is. It’s Shankar Babu and his saved damsel.” He spits on the ground. “While I have not eaten for three days, here you are, with a girl! Do you know what I have sacrificed for this country? Do you know what I have lost? And you gave me opium, but it was a temporary escape. I want what you have. I want food. I want her.” He licks his lips while ogling Avanti.

Then, he charges.

Time suddenly slowed down, and I saw the blade approaching my belly. “STOP!” Avanti squeals beside me. She puts her hand forward as a last protective cover. I see a spark in between her cradled palms. Within an instant, the spark becomes a bright flower of blue flames. The enthralling fire escapes her palms and approaches Shadon Miya like a guided missile. He screams with unbearable pain as the fire engulfs him, turning him into a beacon of orchard red. As we flee, I looked back at him.

His screams had stopped. Sadhon Miya had finally found peace.

We did not talk to each other as we took a tanga to escort her home. She sat beside me. Sweat enveloped her forehead. Her fingers were interlocked, dancing in a nervous, shaking rhythm. She twitched now and then. When lives are as cheap as dirt, this is the first time she had witnessed death. The first time she had killed.

Even though we did not exchange a single word, we both know we cannot tell another soul about this incident. Inside my head, a quiet storm kept brewing.

#

Later that night, when I tried to sleep, I found myself shifting on my bed. My hands crawl through my fumbled hairs for an answer. Pyromancy, if it is, that is as rare as the elusive apes of Himalaya.

The first pyromancer among us was Tenzin. When Raj was a famished serpent swallowing Bengal, he fell through a crevasse and found himself trapped in the dark underbelly of a glacier. In an abyss of plummeted temperature, he immensely concentrated his chakra cores to save his life-force, albeit for a moment. He looked into the eyes of Yama and melted his way out.

He was not the only one who fell. Neither history nor legends told what happened to his wife. It was written he had to kill her, and a part of him, to escape. When he returned to Shangri-La, they presumed frost had taken all his toes and he had observed how blurry was the boundary between life and death. When he returned, Tenzin knew how to transform that concentrated chakra spark into the ignition of a life engine. As an entomologist, he already had profound anatomical knowledge of a particular species of beetle. He chewed his toes and spat them out as organic Molotovs.

He was also our first necromancer. Thirty years later, when he found the frozen corpse, he brought her back. There were some dire repercussions. Only fragments of her soul returned. The shadow of that woman was like a feral creature. It only responded to the scent of raw flesh and answered through growls and screeches. Tormented with grief, he had to again leave her where he had found her. He was afraid, and he erased all the traces of his newfound knowledge. Well, almost all of that.

Life and death are the embodiment of entropy and constancy themselves. And when they meet, combustion happens. Either I am in love with a dead girl or her dying state, and my conflicting chakra gave her this blessing. Either way, I know that I have a lot to discuss, more to unravel.

At dawn, I found I am sinking in the bed drenched with my sweat. I washed myself and went for a walk. The cool breeze soothed my wrecked nerves.

Many moons ago, when I was young and stubborn, just an apprentice under my father, I stumbled upon the redacted records of Tenzin. My father was both furious and afraid when I asked him about that man. I had to dust the entire courtyard alone, for a month, as a punishment for asking such a question. Typically, this would have kept me from asking more. However, I soon found myself digging deep in the library, sneaking in the archive of redacted records. There were monks like me who found out Tenzin’s secret notes. Most of them were simply curious, but some were driven by an urgent, at times vindictive need. All of them were thrown out from their only home.

When my father found me with the dead Siberian goose, placed inside the mantra circle drawn with my blood, the opium I had to consume to perform this ritual, and the records of Tenzin hidden inside the layers of my mattress, he did not ask. Instead, he showed me the trail that connected to the southern alluvial plains and told me how I profoundly failed him as a son. I had only minutes to pack my belongings before others could know. When I walked past the monastery and ascended on the stairs, I looked back at him. His fists were clenched. Tears lensed his eyes. As I walked away, I felt the conflict between archaic rules and paternal love torturing him. But I kept climbing the stairs.

Years later, when the news of the massacre reached me, as natters of the war, I wondered if he foresaw the future and threw me away; or, was this his final punishment, to bear the weight as the last representative of a forgotten culture?

Either way, as I shook my head to get rid of these lice-like thoughts, I found myself standing in front of Avanti’s house. I hesitated and looked at a just-opened tea stall. I silently opened the front gate after quenching my morning thirst with some biscuits and a earthen cup full of milked tea. The entrance was slightly open. I took the newspaper roll from the railings and cleared my throat. Before I knocked, I could hear them talking. Arguing. Quarreling.

“This is how you repay someone, mother, for saving my life?” Avanti protests.

“Have you looked at the faint tattoo on his index figure, the minuscule white lotus? These people are the reason why we had to flee from our homes. They are not saints but monsters. How can you take the side of a man whose cult intended to keep you forever dead?” Sharmila answers. Her voice was like a rusty blade.

I froze before the door.

Sharmila continues, “Yes, I was desperate to seek him out. You were dying. The entire world looked bleak to me. I heard the rumors of his magical treatments, the way his patients are miraculously cured. I expected him to give you some swarnoparni leaves as medicine. I did not expect him to give his damned blood. Neither did I expect you to fall in love with him, a fucking Vajrayana monk. And you, my gullible daughter, are asking me, and the brotherhood, to forget all the things his kind did to us? Your broken heart can mend itself, but he cannot know who we are, what we are. And there is your blemished gift.”

“Let go of me, mother. You are hurting me.”

My heart asked me to barge in; my instinct urged me to run away. I rested my hand on the frame of the door. But I never knocked. Instead, I turned back. I ran away.

My heart is as warm as the summer sun. A grin sits on my lips.

She loves me. SHE LOVES ME!

#

Later that day, I found Avanti at my shop. Her hairs were uncombed, like a crow’s nest. I noticed the suitcase she had carried.

“What are you doing here?” I mouthed and hurriedly pulled down the shutter of my shop.

“My mother knows that you came to our house this morning. Why did you have to have a tea in front of my house where every wall has eyes?” She took a deep breath. “We have to leave, Sankar. Right now. They are after me. They know that you know. They are thirsty for your blood.”

Hours later, sitting inside the crowded bus headed for Burdwan, as she snuggled her hand in mine, she told me about herself and the cult of resurrectors chasing us.

Fighting death is like fighting the tide of time itself. Those who oppose the flow of entropy are against the universe. If Shangri-La remained a place of knowledge as it once used to be, the story of Tenzin would have seeped through the generations as pseudo-mythological warnings. Instead, it was suppressed; all its mentions were suffocated to silence. With time, as Shangri-La became separated from the rest of the world, its teachings became a stagnant, unopposed force for archaic practices, where the disciplines themselves became shallow pools. Justifications were prefabricated. There was little room for questions, analysis, or evolution. Yet, those who wondered about the forces of nature stumbled upon the forgotten philosophies of the ancients, often asked themselves, ‘what are we doing?’

One of them was Sharmila.

Avanti says, “Though I appear a decade younger than you, Sankar, I am of your age. Surely you know what happened to my mother? Back then, she was known as Damini.”

I remember what my father told me once upon a time. Damini was a protégée, the best produced by the monastery in a long time. She fell in love, she married one of her teachers, following the custom. She was pregnant. Then she gave birth to a dead girl.

Avanti did not look at my wide-open eyes. She continued, “She buried me deep in ice and looked for a way to bring me back. Ten years later, when she finally grasped the principles of necromancy, the day you were handed your first scroll, I cried before the world for the first time. I was an average child, Sankar, for I was a mold without a soul, with no drifted memories. If my father hadn’t told your father about me, you and I would have met under very different circumstances.

“Instead, my first memory was of a crescent moon while I am sucking my mother’s dry nipples. My father, because he ratted us out and because the society of Shangri-La was so predominantly patriarchic, managed to save his skin. Wandering, begging to meet both ends meet, in the alleys of Kashi, if those who were banished before had not found us, I would have died again. The world is unfalteringly cruel towards a single mother and her fatherless child. I owe my life to these people, though I loathe their barbaric ways of tantra, and how they exerted revenge by giving the Nazis the address of our former home. I owe my life to you, my love.”

I did not answer. My mouth was both supple and dry. I know why I left all my worldly belongings to the woman living on the pavement who bears my child. I understand why my father quietly made me go.

Things we do for our blood.

I remembered the gold statue of Buddha in the main hall, the library packed with scrolls, the courtyard where we practiced martial art. In this dungeon, we reflected upon ourselves, the cliff opening to the unending stretches of Himalaya where we meditated. Shangri-La is gone, and a part of my soul has vanished with it. Who are we to understand our purpose in this world, merely a conduit of a grander epic? A ripple in the river of history? Perceiving the soul’s work, understanding the bifurcated tributaries of a fragmented human mind should be left for God to understand. We are only children projecting ourselves as adults.

I looked at her and cupped her hands. “Are you happy with me?”

She looked at the bus window, at the landscape marching past us like ramming troops, and nodded softly. “Forever and always.”

#

“I don’t recognize this world,” the man sitting in front of us commented. “I mean, the war, then this wretched dissection of our motherland, will forever haunt us. Even our children.”

Inside the train, people occupied all the available spaces like stacked books. Some sat on the floor; some even hung from the window; some had found a place on the roof. The steam engine roared. This was the last train that will ever leave for Dhaka. Crammed inside such a suffocating place, Avanti tried to breathe clearly. But she dared not to lift her niqab, nor did she ask how long it will take.

After a bloodbath between brothers that had swept the country, simply because they pray to different gods, two independent nations were emerging from the womb of a colonial one, like severed appendages. The Raj was finally going home. The war for our independence and of the world was over. But all that had left us with a catastrophic scar. The man is right; even I, so separated from my past, did not recognize this world.

He spoke again, as if being quiet was like an itch to him, “My name is Habibur Akash Rahaman. These are my two children, Rokeya and Abbas. And you?”

I look at Avanti; I watched her eyes piercing through the narrow opening and absentmindedly touched my newly grown beard. “Myself Shalim Pasupathi Akhand, she’s my begum, Jahanara. Beside her, that’s my son Suleman.” I pat the young girl’s head sitting on my cradle. “She’s Amira.”

A sadness engulfed his face, “My wife died during the Calcutta riots…She…” his voice chocks.

His eldest child removed the tear from his cheeks and whispered softly, “Don’t cry, baba. We will be well. We are here with you.”

Partition, too simple a word, superficial in execution (as the departing Raj had described), is a serrated blade gutting a living organ. It ran through people’s homes, their belongings, and dreams, mutilating futures on both sides, at both frontiers. Millions of stranded, displaced souls like him were on board on trains like these, utilizing every inch available, for their homes have suddenly become an alien and hostile place. Occupying the competed space with them is us.

We were on the run for the past four years. Since Avanti came into my life, I never felt this alive, never felt the desire to peek in the future. As the world around peeled its colonial skin like a rotten onion, we found ourselves content with each other. These were perilous times, and I got her pregnant when we were in Hyderabad. When the Partition was announced, I knew where we had to settle. Outside of their reach, at the other side of a newborn boundary that soon will be heavily fenced, we will finally find stability in our content lives.

Avanti looked at the platform, scanning for familiar faces like her harpooning mother, for I had escaped her claws a few times already by sheer luck. She gently brushes over the burnt skin of my arm, a result of her pyromancy practices.

The platform was a swarm of those who came here and those who cannot go. The train was a beehive without a queen.

When I heared the whistle of the steam engine, a massive weight lifted off from my heart. The amalgamated prayers engulfed the inside air as faithless mantras.

“Habibur Sahib, words cannot describe how sorry I am for your loss. If anything happens, know that your children will be safe with us.” I eye Suleman. “His mother died during the riots as well, my begum whom I never had the chance to marry. Deep down, I do know how you feel.”

And how I have changed.

I found Suleman just where I left him and his mother. He was waiting for me as if he knew I would come. Later, I came to see that he knew all about his unwanted birth. I am grateful that he chose not to blame me but this world.

Rahaman sniffed and asked, “I don’t know what the future holds for us, neither am I betting on any miracle. But thank you, in times like this, your words carry a certain value, values that we have lost.” He gulped and changes the subject. “Where are you going from Dhaka?”

I closed my eyes to see the sacred grove, the fields full of golden rice, the Dhaleshwari river, the supporting riverine system that spreads through the landscape like a capillary network, vividly from my father’s stories – stories that were passed from generation to generation.

I open my eyes and answer him, “It’s Bikrampur. It is where my ancestors once lived. I am going back there to trace my bloodlines.” I affectionately look at my two children from two different mothers. I watched my loving wife and concluded, “And draw a new.”

Tags: English Section, Short Story, Soham Guha, সপ্তম বর্ষ তৃতীয় সংখ্যা